Without even trying, detective stories naturally end up as borderline experimental fiction. They’re the stories most concerned with the act of story-telling itself. I imagine this is why most decent writers love a good detective story. What’s so interesting about them? I love that:

- They’re non-linear. They start with a dead body (middle) and then jump around trying to figure out how that happened (beginning) and hopefully get to the point where justice is done (end).

- They’re Russian Dolls — stories within stories — the story of the crime, the story of the investigation and any number of other side-stories that are dragged into and out of the spotlight by the crime. Multiple frames, multiple narrators.

(One of the earliest detective stories was “The Three Apples” in the One Thousand and One Nights. The Nights itself is one of the most brilliant examples of Russian doll narratives and frame narratives and so it’s unsurprising that it’s here we see the seed of the detective story… It’s also home to one of the great narrators in fiction, a girl who tells stories as if her life depends on it, because it does — the encyclopaedic storyteller Scheherazade)

- And those narrators — Detective stories are full of unreliable narrators spinning contradictory stories. These stories frequently change and its often the very act of the detective comparing different stories that highlights problems and provokes this change–

- — yes, The Detective. A handy figure who helps the audience piece all this stuff together and navigate the tangled mess. He’s part author, part audience, part character himself.

- Detective stories are all about peeling back the everyday surface to reveal the darker, primal underbelly to human life. The subtext to our happy, law-abiding existence. This is same job that authors sign up for!

- As much as any other story, frequently more so, the story of a detective story isn’t contained in its text, or the events that occur in it — BUT in the way in which those events are revealed to the audience and the mental gymnastics the audience performs to arrange and assimilate them.

And as a writer of interactive stories I can’t help loving detective stories even more…

Interactivity can make great demands on a story and it can create issues that threaten to break stories that otherwise work perfectly well in so called linear media. You know, issues such as:

- How to cope with the difficulty of delivering a perfectly organized linear story when a player’s input could disrupt that organization? (Interactivity has historically had more success mining back-story, dolling out non-linear stories and side-stories)

- How to deal with the player himself, a weird combination of character/audience proxy/tool?

- How to build upon the natural interactivity of any story? The component of storytelling that occurs in the audience’s mind, fuelled by their creativity and imagination? Surely interactive media should be able to do MORE with this than their non-interactive cousins?

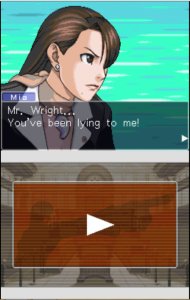

Yes — so the world needs more interactive detective stories. We’ve had some, and some good ones — but I can only really think of a few really good ones. Phoenix Wright is the closest because it gives over so much screen time to the different stories, time frames and testimonies. You get the frames, the narrators and the STORYTELLING that is so important! And Phoenix himself is a fantastic detective — a perfect amalgamation of author, player, tool, detective.

Phoenix Wright isn’t perfect, mind. It’s a product of its original host platform, the (superb) Gameboy Advance. This works for the game — it allows it to be focused on text as its delivery system and its interaction mechanics are locked onto this (even down to the low resolution of the screen enabling the cross-examination mechanic to feel natural when it breaks testimonies down into small paragraphs). The game benefits from the cartoon graphics of the GBA and allows a larger-than-life anime sensibility to smooth over any cracks.

When you try and extrapolate Phoenix away from his original design — away from text, away from his handheld friendly interface — his model doesn’t hold as much water. But this is a worthwhile goal — how to take the essence of what is so magical about Phoenix Wright and apply it to an interactive detective story that is more — for want of a better word — realistic? Realistic when generally applied to video games really is a horrible world, but I guess I mean it — more authentic, more evocative of the world we see around us. No anime, no mini speech bubbles, more nuance to its interaction mechanic?

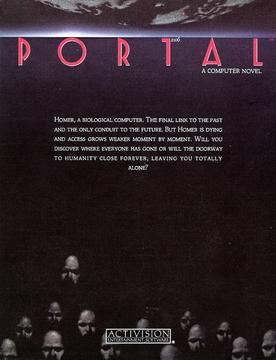

This latter bit is important — there’s a game from 1986 called Portal (not that Portal). It’s a detective story, albeit one where you are trying to solve a murder where the victim is — it seems — the entire human race! It’s a wonderful example of a interactive, non-linear story and how interactivity can help funnel a volume of content that wouldn’t work so well in an non-interactive way. BUT the game is largely about clicking on stuff to proceed. There’s not as much nuance in your interaction as there is in the general structure and your consumption of the story. It’s also pretty ugly now and doesn’t have the pretty sprite character art of a Phoenix Wright to hide its reliance on low resolution text.

Portal is interesting because what it has over Phoenix Wright is that its not in any hurry to be a “game” — there’s no challenge, no skill involved. This is one of the aspects of Phoenix Wright that is most awkward — its desire (as a 2001 GBA game) to be a game, have health bars (!) and offer up a challenge with rewards and punishments. Portal’s lack of gaminess doesn’t hurt it as much as Phoenix Wright’s gaminess hurts that game. But there’s clearly more that can be done with the interactivity than Portal does — and from the comfort of the 21st Century and its not-game friendly landscape, it doesn’t need to be about challenge and skill.

I’ve spent so much time and energy trying to answer the question: “What does a realistic Phoenix Wright look like?” I recently realized that I’d been going about it the wrong way — I was adding on complexity to Phoenix Wright, trying to add layers to fix problems — which only compounded its sins. When I realized I should be simplifying Phoenix Wright that’s when I actually started to make progress towards an idea…