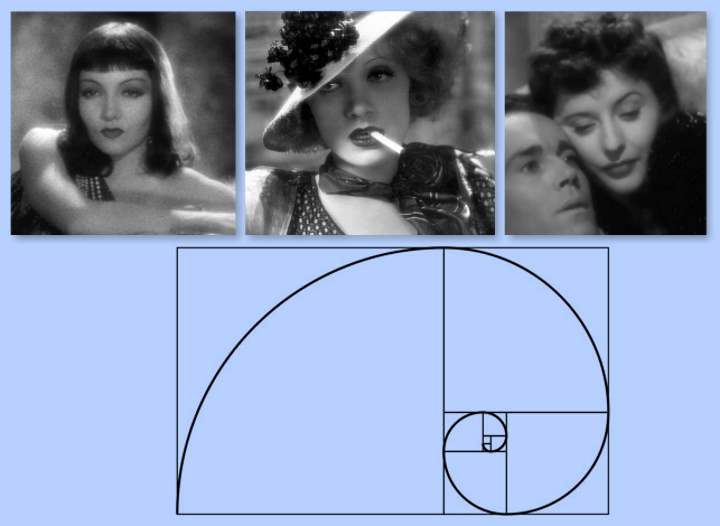

Before HER STORY there was The Architecture of Pan. This was an indie game idea I was kicking about for a bit. An exploratory horror game set in an architect’s 3D visualisation of a non-Euclidean apartment. The apartment was a room-shaped nautilus shell, a digital hidey hole for a hibernating Vampire who was waiting out the 21st Century. The game would have been a maze of sorts as you figured out how to penetrate deeper into the apartment to reach its center. It was a chance for me to make use of (subvert) all the Vampire lore I’d somehow soaked up over the previous years and create a puzzle game where the puzzle was executed entirely using the core navigation controls. If I’m being honest it was also a brain dump of all my favourite female anti-heroes from pre-code movies.

Pre-code movies were full of titillation, but their strongest female characters oozed I-really-don’t-give-a-fuck attitude. Also: a nautilus shell

The core mechanic was neat but I grew dissatisfied with the game because it was too ‘easy’ to make. The combination of simple/deep puzzles with chunked narrative is a winning formula — emphasis on formula. I was particularly uncomfortable with the reliance on bread crumbs of narrative just like every other game with diary pages or variants thereof. I’ve made two Silent Hill games with particular reliance on this technique and it works — little bits of narrative, deliberately set up in a particular order so you get your set up, your complications and then your pay offs. It continues to work to this day such that it’s one of the few mechanics that Gone Home didn’t throw out of the ‘Shock template. But when you strip things down that much, it does start to raise questions, like: why isn’t this just a BBC4 radio play? As a player I start to separate out the diaries from the game — and focus on one or the other. In The Swapper I grokked the puzzles and the narrative was a distraction, easily discarded as a wrapper. In Gone Home I was just hunting for the diary pieces and the house itself became a museum that housed them. This is more my fault than a problem with those games in particular: my jaded brain acknowledges, emphasises the contrivance and the oil and water separate. So I packed my frenzied pencil sketches into a manilla envelope and put The Architecture of Pan to one side.

But something lingered. Surprisingly, what lingered were the narrative bits — the Vampire and her testimony. I was attached to the idea of testimony as a pure form of story — and a direct dialogue between character and audience.

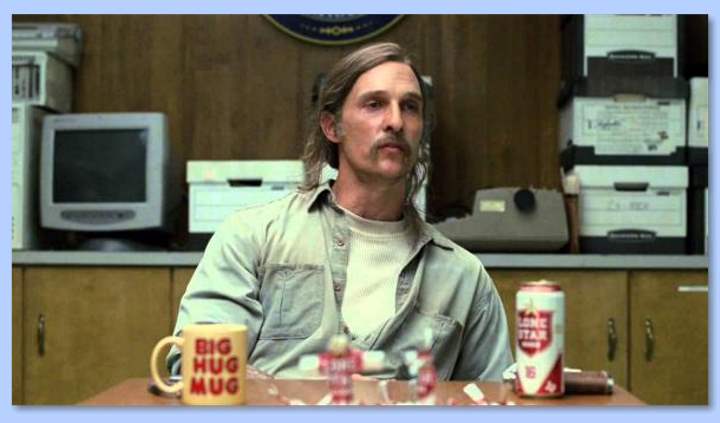

The early episodes of True Detective are a wonderful example of direct testimony and subtext

I decided to tackle my discomfort with story-through-diaries head on. Flooding therapy. I would make a game that was just the diaries (kinda). So I stripped it down till it was just a BBC 4 radio play and started to ask the same questions again: why isn’t this just a radio play? How do I do something with this that can’t be done in a radio play or a book? I started to sort through the clichés that hover around these sorts of questions. “A book is interactive — you choose to turn the page.” “A book has choice — you can choose to stop reading, or to skip ahead.” “You could read the last page first, if you wanted.” These statements are true, but false — there’s a contract that you enter into and the ordering of the pages makes it very clear that you are supposed to read in order. You could read the last page first, but why the fuck would you? The page ordering makes it very clear you shouldn’t. There are works which encourage you to break these rules but they require some effort on the part of the reader. So now I’m thinking about what makes interactive things better. It’s not the freedoms, but the restrictions, perhaps — or rather the interactive thing’s ability to reconfigure itself to impose restrictions on the audience. A simple example: digital choose-your-own-adventures are superior to their paper cousins because they can hide the other pages, they can force you to stick with your choice and move on. They blinker your view of the book and they disallow you from turning back the pages. This creates consequence and involvement.

So I pushed further, tried to imagine ways of imposing restrictions on the player’s reading of a hypothetical book. Imagined ways of reading that are impossible on the page. I wondered about a book that reorders itself based on the angle you view it from. Perhaps here was a device that could deliver the concept of testimony that I had fallen in love with…

Next Time: how to allow players to view a story from an angle and the magic of incantation

NB: HER STORY isn’t about a Vampire. And although I’m talking about books and radio plays, it’s neither.